Image

By Ken Hamilton

Special to the Express

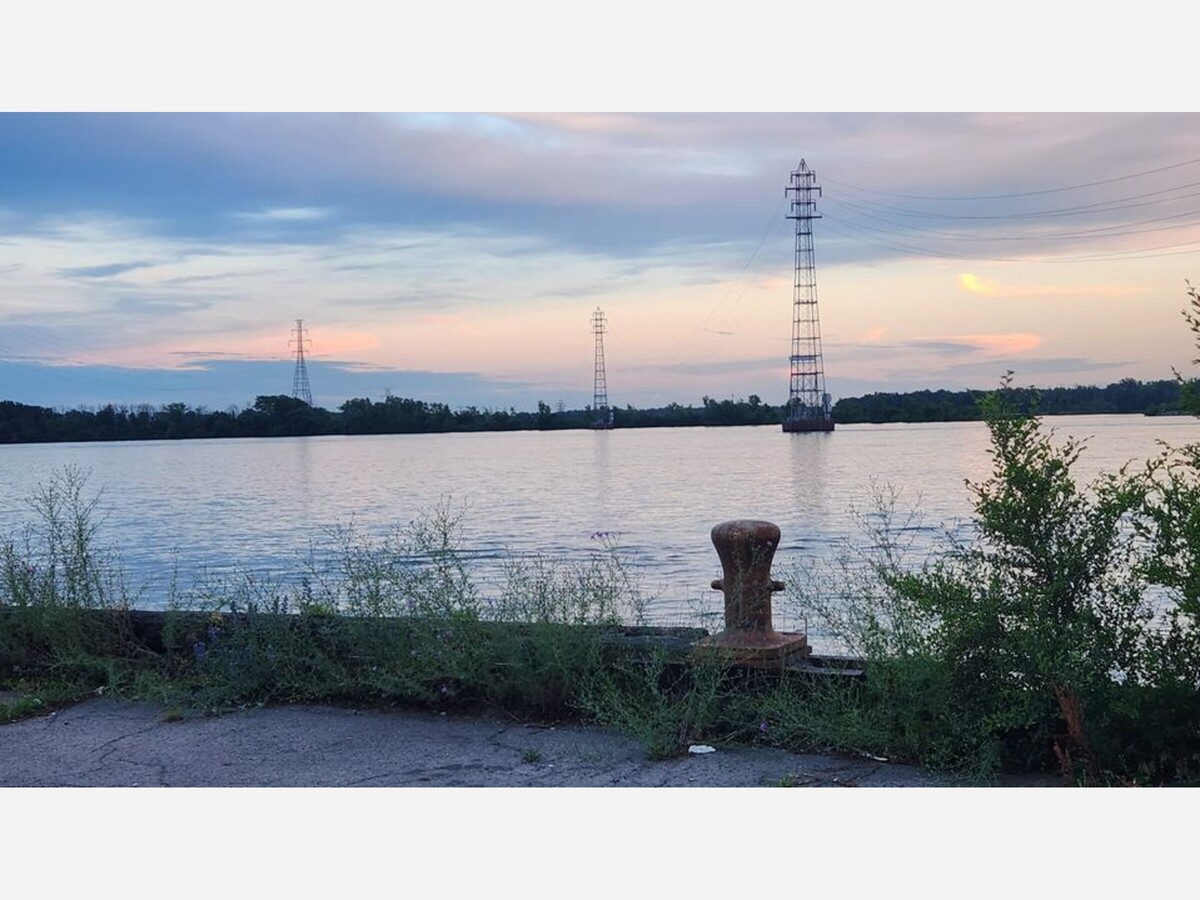

A lonely bollard stands at the former Hooker Chemical Company Dock, waiting for a barge to be pushed up and tied to it.

It is a sentry of a proud past and profitable time when the city of Niagara Falls was bursting at its seams with family-building and community-building employment opportunities. "We had it all," said one old-timer. "My wife would fix and fill my lunchbox for me to go to work in one factory, and the next day she'd do the same as I went to another factory where more of my friends worked."

He then said that, "Then we had everything. Over 100,000 people living in this little city. Jobs all over the place."

"On Highland Avenue," he said, "there was a Union Carbide factory where they made graphite products at one plant, and a sister plant almost right behind it on Hyde Park Blvd. that made different graphite. Between the two was the Pittsburgh Metallurgical plant and General Abrasives. Across from the Pittsburgh plant to the west was a Chisholm Ryder plant where they produced tractors, and south of them was the Autolite factory where batteries were made for tanks, jeeps, ships, all kinds of military and civilian needs. National Lead company, and the Vanadium plants were east of the Boulevard."

"All told," he said, "there were 15,000 jobs on that triangle of Highland, Hyde Park Blvd, and College Avenue."

"There were 30,000 jobs down by the river," he said. "Too many plants to name: Acheson, Carborundum, Dupont, Olin Matheson, to name a few. But the king of them all was the Hooker Plant, and now it too is gone."

The old man almost sobs as he thinks of what is left. "A city that can't even feed itself. It's just now a shallow muddy money pit that carries more water past it in the Niagara River than the Hudson River carries past the high skyline of New York City."

"Gawd," he cries out. "What have we done to deserve this? Our city is little more than a beggar sitting in the shade of a derelict building with a Sombrero on our heads, a light blanket around our bodies, and with our tin cups stretched out to catch the coins that the tourists throw -- most of which are no better than ourselves -- as they take the cheapest vacation that they can take with their kids, driving their own vehicles for their annual two-day respite from their own miserable lives."

Yet, there stands aside the mighty Niagara River, nearly producing on both its sides more electricity than anywhere else on earth in the short distances between them, and we prefer to be beggars.

The old abandoned bollard stands alone, unused, and no hope for barge or ropegazing out at Grand Island and the electrical transmission towers that carry electricity, dollars and hope, from the city to far off places to make other places more profitable. Some of the money does come back much like an empty soda bottle, making us feel lucky that we can turn it in to recover the five-cent return at the store.

"The area was once filled with rail yards," the old man says. "We were once a value-added production place. Now, just a repository for the underprivileged and those who prey on them, in the streets and in the voting booths.

We are just a wannabe, with wannabes in charge."

And the old rusting, lonely, but still strong bollard stands there on the dock, looking out at the down-river mists, and at the towering buildings on the Canadian-side of the international border, and at the power towers that carry our fortunes elsewhere.

Perhaps it is here, as a reminder that we could still be as prosperous as once we were, back in the old days when we cared more about independent families -- as there are on Grand Island -- than we care about people no better than ourselves, telling us how pretty we are in that tiny sector of Dante's Paradise Regained, and scorning the massive size of abandonment in the hell of bad public policymaking in Dante's Paradise Lost.

I hear overhead the squawk of a passing seagull.