Image

By Jeffery Flach

Gorgeview essays

This essay adds a new bird to the series not as a detour, but as a continuation.

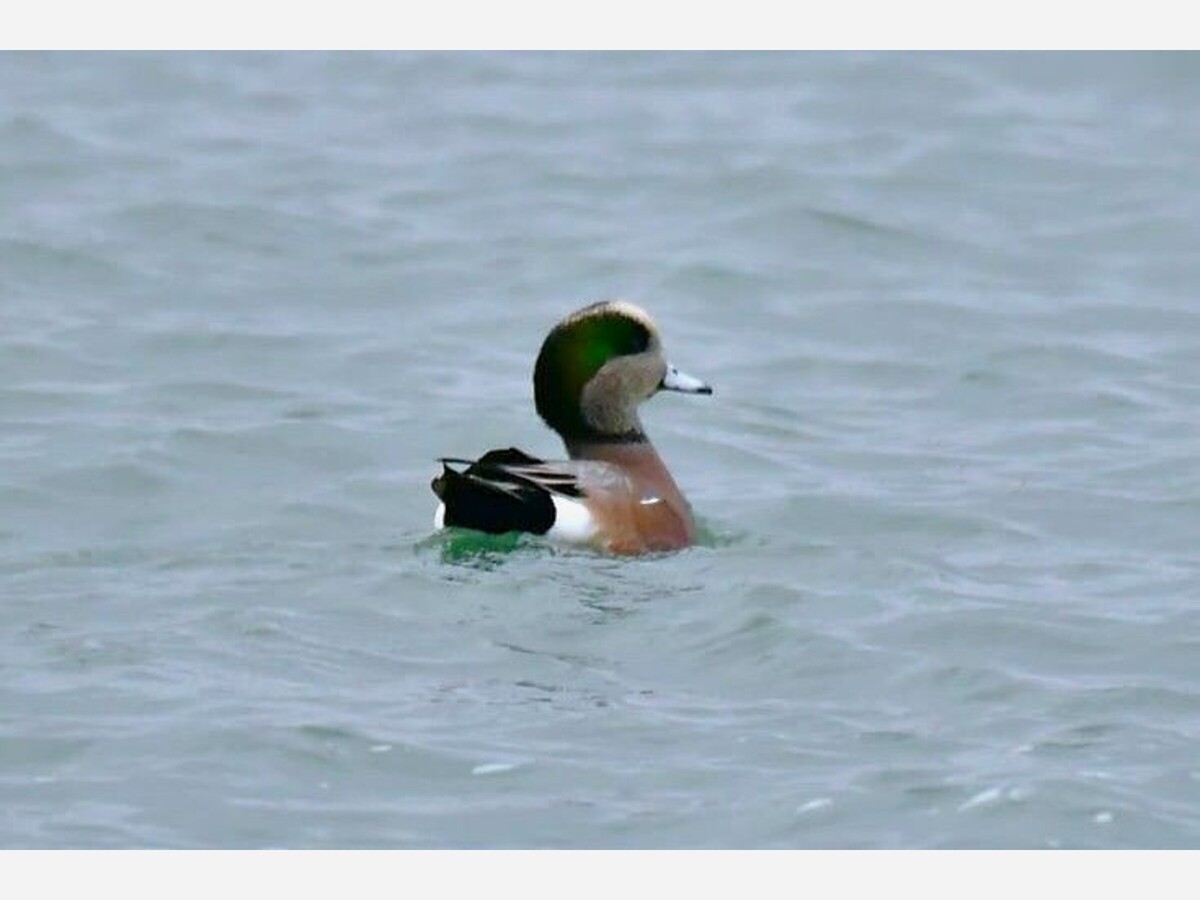

The widgeon is another “winged wonder”—a bird that captivates the human imagination precisely because it feels both local and slightly unreal. It belongs here, moves through our waters, and appears as part of the seasonal pulse of the Niagara River corridor. Like the other birds in this series, it is not merely an animal. It is evidence that life concentrates here. Evidence that Niagara is a living system that changes with the calendar and rewards those who experience each season.

A visitor who learns to look for a widgeon is not just looking for a duck. They are learning how to see Niagara differently, not as a tourist strip, but as a city embedded in ecology. That shift in perception is economically powerful because once a person realizes Niagara has a seasonal ecology worth returning for, the Falls becomes the gateway, not the endpoint. The waterfall becomes piece of the visit, not the whole story.

If Niagara Falls wants to reclaim a global identity worthy of the world’s attention, we must stop acting like our greatest asset ends at the guardrail. We must understand ourselves more deeply: our history, and our environment. We must become stewards not only in the moral sense, but in the practical sense, competent, literate, and deliberate.

Birds are the simplest starting point. They are the easiest door into ecological literacy. They are an efficient trigger for curiosity. And curiosity is the engine of dispersal, repeat visitation, and off-season demand. The widgeon is one more proof that Niagara is not a one-time experience.

It is a place of wings and wonders—season after season—waiting for us to notice what we already have, celebrate it, and share it with the world.

Niagara Falls is famous enough that people will cross oceans to see it but they don’t venture far from it because of our failure to share our story. When a place becomes known for a single icon, it can accidentally teach the world that everything beyond that moment is irrelevant.

That is not true here. Niagara is not a single view. Niagara is a living system. The entire system is relevant. The falls are the invitation the ecology is the story, the geology, the natural and human history are subplots. Our birds make compelling characters in that story, the protagonists woven through the entire arc of history here and continue playing compelling roles in our everyday lives. From Widgeons to Eagles, from Cardinals to Seagulls, Egrets to Herrings…over the last nine essays, I have tried to make one argument from multiple angles, using different birds as different doors into the same house: if we want Niagara Falls to be economically healthier, more resilient, and more respected, we must learn our environment, understand the seasonal patterns that shape it, and share that living story with the world in ways that invite people deeper into the city.

The Waterfalls invite the world to our the city. Birds are an invitation into and throughout the city. They are visible. They are seasonal. They are local. They are free. They are compelling to human attention. Attention becomes movement. Movement becomes dispersal. Dispersal becomes economic activity, and reasons to return when the season changes and the cast of winged wonders change with it.

If our identity is only “the waterfall,” we will continue to suffer from the same structural weakness: concentrated tourism that accelerates visitors through a narrow corridor and ejects them. That is why this conversation is not merely “birds as a hobby.” It’s “birds as a lobby.” It is about birds as a civic literacy program. Birds are an accessible way for residents to learn how the Niagara River corridor functions, how seasonal cycles shape what appears. Only when the locals understand this can they effectively share it. The question is whether we will give the world a deeper, more meaningful story to follow. A story that benefits us as much as it inspires them.

This strategy works especially well with an underserved segment of tourism: birders, naturalists, wildlife photographers, and ecology-minded travelers. They are more likely to travel in the off-season, more likely to stay longer, more likely to return repeatedly, and more likely to promote a location through authentic storytelling that costs the city almost nothing in advertising. In other words: this is tourism that markets itself if we give it a narrative.